Writeup Crypto Ctf

Intro

On the 2019-08-10 i participated in the First Crypto CTF. Actually I had something else planned for the weekend, and so I could not hack the whole time and just hacked around six hours. In fact, I solved only the easiest challenges. Nevertheless, it was fun and I learned something. Thanks to the organizers for finally having a crypto ctf without people complaining about crypto.

As usual in CTFs there were a bunch of challenges and if you solved one correctly, a special flag in form of a binary string appears from somewhere. This flag can be submitted in the web-interface and your team gets points.

This post contains my writeup. If you want to play around with the challenges, you can find them at the following links. If you want to read other writeups, go here.

- alone in the dark

- bad zero

- cat sharing

- clever girl

- fast speedy

- galof

- midnight moon

- oliver twist

- roXen

- stuff

- super natural

- time capsule

Decode Me

For the challenge “Decode Me”, there was only a string given:

D: mb xwhvxw mlnX 4X6AhPLAR4eupSRJ6FLt8AgE6JsLdBRxq57L8IeMyBRHp6IGsmgFIB5E :ztey xam lb lbaH

This looks a little bit reversed, especially with the “:ztey” part. Usually colons are at the end of words.

Habl bl max yetz: E5BIFgmsGI6pHRByMeI8L75qxRBdLsJ6EgA8tLF6JRSpue4RALPhA6X4 Xnlm wxvhwx bm :D

Looks better. My guess was that the first part is “Here is the flag:”. Maybe something easy such as a caesar cipher. A nice tool to play around with such strings is GCHQ’s Cyberchef. When I use the caesar cipher with a displacement of seven symbols (or a key of H), I get the following.

Ohis is the flag: L5IPMntzNP6wOYIfTlP8S75xeYIkSzQ6LnH8aSM6QYZwbl4YHSWoH6E4 Eust decode it :K

The “Ohis” should probably be “This”, and “Eust”, should be “Just”. So we are in Vigenere territory. The key for vigenere is thus “MHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHH”.

This is the flag: L5IPMntzNP6wOYIfTlU8S75xeYIkSzQ6LnH8aSM6QYZwbl4YHSWoH6E4 Just decode it :K

The part in the middle is valid base64. However, decoding it yields just some unreadable stuff. I tried interpreting it as x86 opcodes, but there were a few invalid instructions so I thought this is too far-fetched. I also tried decrypting the numbers in the base64, as it is unclear how to treat numbers in vigenere. But that also did not work.

~/cryptoctf2019$ base64 -d <(echo -n "L5IPMntzNP6wOYIfTlU8S75xeYIkSzQ6LnH8aSM6QYZwbl4YHSWoH6E4") > decodeme_debase64

~/cryptoctf2019$ file decodeme_debase64

decodeme_debase64: data

And then i was stuck.

After the ctf was over I read some writeups. Maybe I should have seen that :K is a very awkward smiley. Then, I may have realized, that the vigenere key is not “MHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHH”, but “H” for upper case letters and “M” for lower case letters. As I knew that the flags start with “CCTF”, I could have base64-decoded that part and thus recover the key for the numbers. Putting these three keys together, gives the correct decryption keys.

Permutations Game

For the permutations game it was necessary first to connect to a server.

~$ nc 167.71.62.250 20029

------------------------------------------------------------------------

Playoff Permutations Game

------------------------------------------------------------------------

Submit a printable string X, such that sha1(X)[-6:] = 918957So we first had to compute a proof of work.

For this, one has to choose a random printable string X, hash it and

check if sha1(X)[-6:] = 918957. There is no more efficient way to

compute this if (and only if) the hash function is secure.

The number that has to be reached is usually called target.

I first had some code to generate random strings found in a

stackoverflow article. While this code could theoretically generate a

wide number of random strings, it was really slow. The problem was,

that it uses stuff such as random.choice and join. As there was

another challenge which also used a proof of work, it made sense to

improve the speed of this subroutine.

My alternative was to use a uuid such as

a05073b2-0bd1-4ded-89af-0c44eb142ea4 instead of choosing a printable

string completely at random. Interpreting the uuid as hexadecimal does

not generate all possible printable strings of a given length, but is

very fast, as most of the stuff when generating a uuid in Python

happens in C.

So, I did some benchmarking code to check if my function was really

faster.

import time

import string

import random

def random_ascii_generator1(size=32, chars=string.ascii_uppercase + string.digits):

return ''.join(random.choice("ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZabcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz1234567890") for _ in range(size)).encode('ascii')

def random_ascii_generator2(size=32, chars=string.ascii_uppercase + string.digits):

return ''.join(random.choice(chars) for _ in range(size)).encode('ascii')

# https://stackoverflow.com/questions/2257441/random-string-generation-with-upper-case-letters-and-digits

import uuid

def random_ascii_generator3():

return uuid.uuid4().hex.encode('ascii')

for algo in [random_ascii_generator1, random_ascii_generator2, random_ascii_generator3]:

start=time.time()

for i in range(100000):

algo()

end = time.time()

print("time elapsed for {0}: {1}".format(algo.__name__, end - start))The results of a sample run look as follows.

time elapsed for random_ascii_generator1: 2.5260610580444336

time elapsed for random_ascii_generator2: 2.780190944671631

time elapsed for random_ascii_generator3: 0.33684778213500977

Thus, I used uuids as random printable strings. After submitting a valid proof of work the following menu was presented.

|-------------------------------------|

| Options: |

| [S]how encrypted msgs! |

| [G]uess the key |

| [E]ncryption function |

| [Q]uit |

|-------------------------------------|

Pressing E showed the following.

def gen_divan(l, n):

assert l < n**2

key, F = random_permutation(n), []

for _ in range(l):

g = random_permutation(n)

F.append((str(g.to_image()), str((key * g * key.inverse()).to_image())))

return key, FPressing S showed the following.

g = (13, 6, 4, 18, 38, 1, 39, 22, 36, 10, 23, 14, 28, 12, 31, 34, 2, 30, 3, 11, 33, 20, 9, 26, 17, 8, 40, 25, 32, 5, 19, 15, 37, 7, 35, 21, 27, 16, 29, 24)

key * g * key^(-1) = (29, 8, 34, 7, 28, 19, 23, 4, 9, 6, 37, 14, 20, 32, 11, 30, 27 , 18, 5, 13, 40, 35, 36, 38, 3, 10, 39, 31, 26, 12, 24, 21, 1, 33, 15, 17, 2, 25, 22, 16)

g = (36, 14, 39, 37, 25, 35, 17, 30, 29, 19, 15, 22, 32, 6, 12, 38, 7, 4, 28, 27, 40, 1, 23, 11, 5, 3, 13, 24, 20, 21, 9, 2, 34, 31, 26, 33, 8, 10, 1 8, 16)

key * g * key^(-1) = (33, 1, 35, 24, 13, 36, 3, 17, 4, 25, 7, 34, 23, 26, 29, 19, 5, 31, 32, 21, 9, 15, 40, 10, 38, 14, 27, 39, 28, 8, 30, 20, 18, 12, 2, 37, 16, 11, 6, 22)

g = (3, 28, 11, 33, 6, 27, 21, 26, 12, 22, 5, 10, 1, 32, 8, 9, 36, 38, 31, 20, 2, 24, 13, 19, 7, 4, 14, 25, 40, 37, 18, 15, 34, 16, 35, 29, 17, 30, 39, 23)

key * g * key^(-1) = (39, 27, 11, 38, 7, 2, 4, 31, 9, 10, 14, 26, 18, 22, 29, 40, 34, 23, 5, 19, 37, 6, 8, 17, 33, 35, 16, 25, 1, 12, 28, 30, 3, 21, 32, 36, 20, 15, 13, 24)

| please send M to see another part of encrypted msgs!!

All of this took a long time to achieve, as computing the proof of work took around one minute. And then it was impossible to test the code fast.

So, translating all this computer science gibberish to math, the key is a random permutation \(k\in\mathbb{S}\). What we get are a bunch of values \(g\in\mathbb{S}\), together with \(kgk^{-1}\) and we should compute \(k\) from this. And this is where I got stuck.

We can find a value \(x\in\mathbb{S}\) such that \(x\cdot kgk^{-1}=1\). This is easy. Then \(k=xkg\), as inverses are unique. However, we are unable to compute \(k\) through this.

My next idea was to somehow chain the different \(kg_i k^{-1}\). For example \(kg_i k^{-1} \cdot kg_j k^{-1} = kg_ig_j k^{-1}\). But I also fail to see how this gives us \(k\).

In the following is my code. Most of the effort was put in the proof of work and for the remainder I simply lacked a good idea.

ip='167.71.62.250'

port=20029

import socket

import re

sock = socket.socket()

sock.connect((ip, port))

print(sock.recv(256))

information = sock.recv(256).decode('utf-8')

print(information)

match=re.search('Submit a printable string X, such that (.*)\(X\)\[-6\:\] = (.*)', information, re.MULTILINE)

algo=match.group(1)

target=match.group(2)

print("[*] algo needed: {0}".format(algo))

print("[*] target needed: {0}".format(target))

import uuid

def random_ascii_generator():

return uuid.uuid4().hex.encode("ascii")

import hashlib

algo_matching = {"sha1": hashlib.sha1,

"md5": hashlib.md5,

"sha224": hashlib.sha224,

"sha256": hashlib.sha256,

"sha384": hashlib.sha384,

"sha512": hashlib.sha512

}

candidate_hash = ""

while not candidate_hash[-6:] == target:

candidate_string = random_ascii_generator()

candidate_hash = algo_matching[algo](candidate_string).hexdigest()

print("[*] PoW found")

sock.send(candidate_string +"\n".encode("ascii"))

print(sock.recv(256).decode('ascii'))

print("[*] Sending S")

sock.send("S\n".encode('ascii'))

print(sock.recv(4096).decode('ascii'))

print(sock.recv(4096).decode('ascii'))

print("[*] Sending M")

sock.send("M\n".encode('ascii'))

print(sock.recv(4096).decode('ascii'))

print(sock.recv(4096).decode('ascii'))

print("[*] Sending M")

sock.send("M\n".encode('ascii'))

print(sock.recv(4096).decode('ascii'))

print(sock.recv(4096).decode('ascii'))

print("[*] Sending M")

sock.send("M\n".encode('ascii'))

print(sock.recv(4096).decode('ascii'))

print(sock.recv(4096).decode('ascii'))

print("[*] Sending M")

sock.send("M\n".encode('ascii'))

print(sock.recv(4096).decode('ascii'))

print(sock.recv(4096).decode('ascii'))

#print("[*] Sending E")

#sock.send("E\n".encode('ascii'))

#print(sock.recv(256).decode('ascii'))

#print("[*] Sending G")

#sock.send("G\n".encode('ascii'))

#print(sock.recv(256).decode('ascii'))

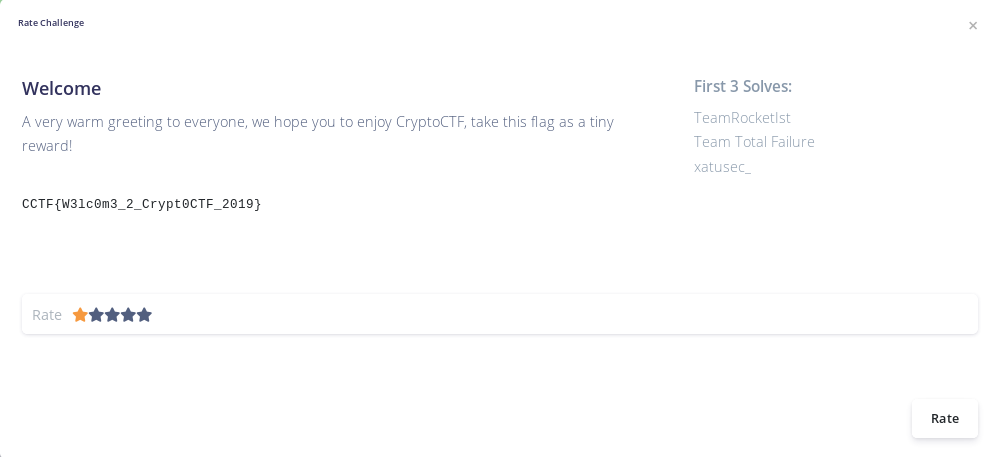

sock.close()Welcome

This was the first challenge I solved :D

The second successful challenge was, that I filled out their survey.